- Stock Picker's Corner

- Posts

- Why This AI "Bat Plane" Could Ignite My Top Defense Stock

Why This AI "Bat Plane" Could Ignite My Top Defense Stock

The company we brought you is building AI drones and hypersonic rockets — and new factories to keep up ...

It’s called the X-BAT.

It was just unveiled.

And it’s a stealthy, “autonomous” combat jet whose ability to take off and land with no runway will be a game-changer in future battles — especially if the United States and China square off in far-off skirmishes involving Taiwan or the South China Sea.

The X-BAT is one of the newest entrants into the fast-growing markets for “Collaborative Combat Aircraft” (CCA) or “Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles” (UCAVs). It was developed by Shield AI, a 10-year-old San Diego aerospace innovator that’s still privately held, but keeps delivering hit after hit for the wars of the future.

“At Shield AI, we believe the greatest victory requires no war. To make that belief real, we’re executing a simple but ambitious master plan: prove the value of autonomy, scale it across domains, and reimagine airpower,” said Brandon Tseng, a former U.S. Navy SEAL who is Shield AI’s co-founder and president. “X-BAT represents the next part of that plan, expanding U.S. and allied war-fighting capacity through a transformative, runway-independent aircraft. Airpower without runways is the holy grail of deterrence. It gives our forces persistence, reach, and survivability, and it buys diplomacy another day.”

The X-BAT had its “public reveal” last week.

As a guy who grew up the son of a defense-industry engineer (and who also spent years covering defense and aerospace projects during my reporting days), I can tell you that this is a great story.

But for all of you members of SPC Premium, it’s also an important story — for two specific reasons:

First, Shield AI has a partnership with one of the companies in the SPC Model Portfolio.

And the “combat case” for the X-BAT also confirms the need for several of the weapons-systems programs our “portfolio company” is working on.

That company — which has been a big winner for you — has several important new developments it’s time to share.

So let’s get started.

Keeping “Your Guys” Alive

Since airplanes first saw use in combat, war planners have wrestled with two crucial questions:

How do we build combat planes that can take the fight to my enemy?

And how can we best protect the pilots and flight crews as they fly those missions?

Two simple questions — neither with easy answers.

You’re talking about building bombers that can carry heavy weapons loads (bombs and missiles) to the target. And fighter planes that can protect those bombers, ward off interceptors or hit at specialized targets or enemy troops on the ground.

Range and fuel loads are a factor. So is protection — be it armor, countermeasures, ammunition capacity and more.

In the old days, bombers had longer ranges, meaning you’d have to base the fighters closer to the target areas — and plan for the two groups to link up. Runways were the “wild card.” Putting them closer to the enemy made them vulnerable to enemy attacks that could put the runways out of commission.

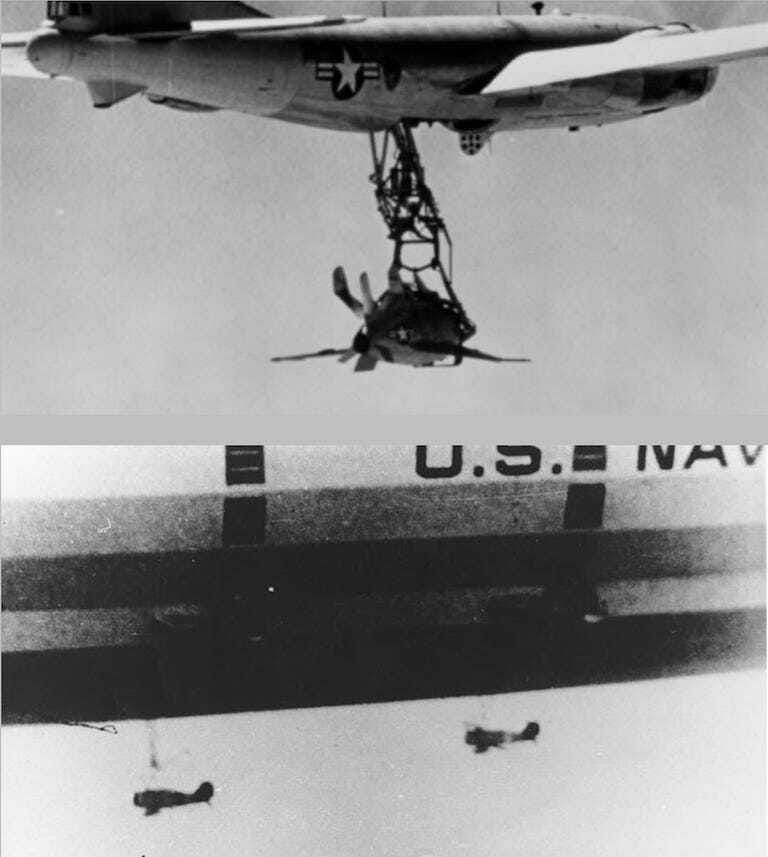

Engineers came up with all sorts of gimmicky solutions. During the Golden Age of Aviation (between the world wars) — and again during the early part of the Cold War — designers actually looked to hang the shorter-range fighters on “trapezes” beneath airships like the doomed USS Macon, or nuclear-armed long-range bombers.

During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Force developed auxiliary “drop tanks” and a remarkable long-range fighter called the P-51 Mustang, that was able to accompany American heavy bombers from England to strategic targets deep in Germany — and back. Bomber crews referred to those escort fighters as “Little Friends” and understood that they’d survive longer because the Mustangs were there.

After World War II, as weapons got more sophisticated (for instance, as missiles got more accurate), air bases and their runways became more vulnerable. So engineers again hit the drawing boards and tried to develop combat planes that could take off and land vertically — known as VTOL in defense-sector parlance.

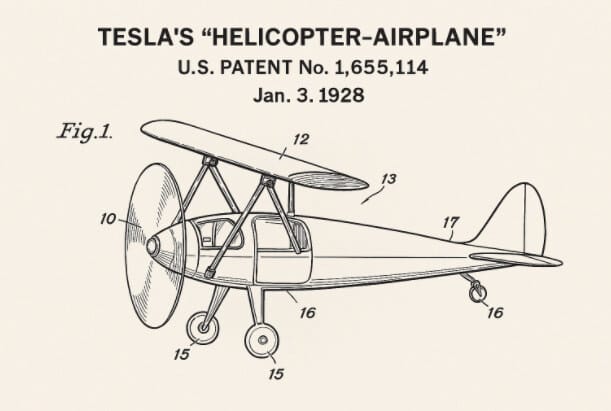

Inventor Nikola Tesla noodled around with a “helicopter-airplane” VTOL design in the late 1920s.

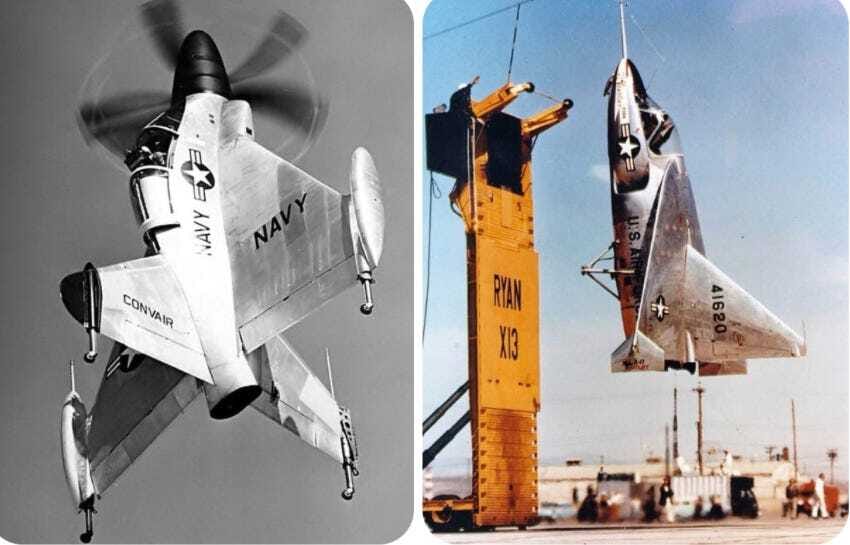

And Cold War engineers created such prototypes as the Convair XFY Pogo (left) and the Ryan X-13 Vertijet (right).

The China Syndrome

Fast-forward to the present, and those “old problems” are delivering new twists.

America, the “carrier-strike group,” is the key to “force projection.” With a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier (with about 70 aircraft), an accompanying attack submarine, a mix of guided-missile cruisers, destroyers and frigates and a couple of supply ships, the CSG lets America make war wherever needed. There’s also the U.S. Air Force, which has its own fighters and an array of strategic bombers. Aerial refueling (from big jets that are like flying gas stations) makes it possible for jets to take off from the Mainland USA and hit targets anywhere around the world.

Once again, it’s about getting close enough, flying far enough and protecting air crews.

Given the increasingly flinty rapport between Washington and Beijing — and China’s covetous designs on Taiwan — the potential for a dustup in the South China Sea just keeps climbing.

And China has spent the last 15 years preparing just for that possibility — using something defense analysts refer to as an “area-denial strategy.”

Beijing built — and militarized — “islands” in the South China Sea … in essence, forward bases that create an armed buffer around Mainland China.

The Chinese military developed hypersonic anti-ship missiles known as “carrier killers” — which fly at many times the speed of sound, at wave-top level, and with a lethality that can wipe out pieces of a “strike group.”

These are known as “standoff weapons” since they force the carrier strike group to operate from much longer distances. That’ll force American strike aircraft to refuel going to and from target areas — making the aerial tankers (and their crews) more vulnerable. And the now-longer combat missions will give enemies more time to shoot down the American fighters and bombers and more chances to kill their crews.

To solve this “old-problem/new-twist” dynamic, engineers are applying the latest technology to the WWII solution — the “Little Friends.”

They’re creating the “Loyal Wingmen” — collaborative drones that can fly ahead of, around and with manned combat aircraft.

Think about it. You can create drones that serve as:

Robotic aerial tankers, lurking around the entry and exit of defined combat zones — to refuel the planes flying long missions, without exposing human pilots to harm.

“Advance scouts,” flying ahead to scope out air-to-air missile, radar sites and other air defenses, weather and the status of intended targets — relaying crucial insights back to the attack force and even “softening up” the target for that main strike force.

Decoys, flying to false targets in a way that pulls defenses and interceptors away from the real objective.

Sacrificial “screens” — creating a kind of surrounding, protective cocoon around manned combat planes and confusing defenders on the ground or in the air.

That’s what we mean when talking about UCAV or CCA drones, which can operate autonomously or under the control of human pilots or specialists back on the ships or at the home bases.

That’s a vast oversimplification, I know. But you get the idea.

And it’s part of the goal of the X-BAT, whose VTOL abilities can let them fly from forward areas without runways, from ships (besides aircraft carriers) and perhaps even from submarines. And that includes “drone ships,” too.

The X-BAT itself is impressive — as an “airframe.” But what’s inside is a differentiator — and leads us to the SPC portfolio company.

The “Operating System” For Warfare

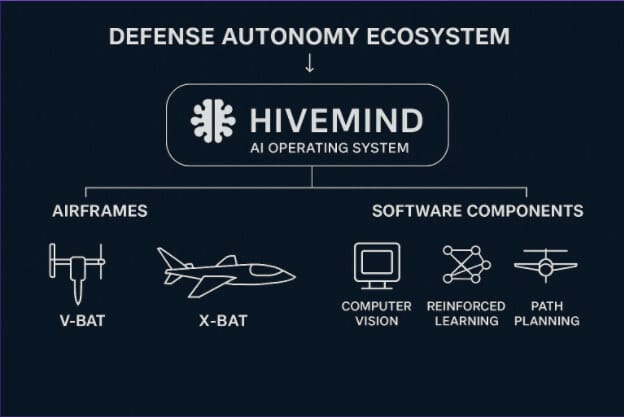

One of Shield AI’s greatest innovations — and the technical “elixir” that makes it “go” — is something called “Hivemind.”

It’s kind of like the “operating system” that makes a computer work. Except this “operating system” is AI-enabled and turns a jet like the X-BAT into an autonomous system that can make real-time combat decisions without human input, without GPS reliance during a communications outage.

It can also act as a collaborative “digital wingman” to manned aircraft.

The U.S. is just starting to plumb Hivemind’s depths.

Last year, during a test of the joint DARPA/USAF “Air Combat Evolution” (ACE) program, a drone version of the F-16 Fighting Falcon jet (known as the X-62A VISTA) flew autonomously with Hivemind serving as its AI pilot. What’s more, the X-62A went up against a human-piloted F-16 in a classic “dogfight” (with the jets squaring off in visual range).

The “winner” wasn’t disclosed. But several years before, when AI and a human pilot squared off in a simulator dogfight, the AI jet won. And Hivemind uses “reinforcement learning,” which is descended from the technology used in that 2020 dogfight test.

That brings us to the SPC Model Portfolio company — which is integrating Hivemind into several of its programs.

Subscribe to our premium content to read the rest.

Investing is simple – you're either a Wealth Builder or a Wealth Killer. As Wealth Builders, we find the best storylines – AI Era, Biotech Blockbusters, Private Equity Tidal Wave, Commodity Supply Shortfall, and more – leading us to the best stocks and assets. We “accumulate” wealth – foundational stakes, recurring purchases, and opportunistic buys on pullbacks. We hold stocks for 3 to 10 years. We think for ourselves, stick to our strategy, and play our own game. SPC isn’t for everyone, and that’s okay. Like-minded Wealth Builders understand our value, which is why folks from everyday investors to CFAs to venture capitalists have joined SPC Premium. Per Beehiiv's policies, all sales are final and fully earned upon receipt. No refunds for any purchase under any circumstance.

Already a paying subscriber? Sign In.